The Impact of the U.K. Diverted Profits Tax

DPT was first introduced in response to Google’s public stance that it was paying tax in all jurisdictions where it operates in accordance with the law and that governments should change their laws if they wanted a different result. Hence, the DPT is often referred to as “the Google Tax.” DPT applies to profits “diverted” from the U.K. after 1 April 2015. If HMRC issues a DPT notice, tax at 25% will be due on the profits HMRC considers diverted, without any reduction for losses or other attributes. The company must pay the tax up front, long before any detailed dialogue with HMRC and any ultimate appeals process can be brought to bear. Where time limits for HMRC to issue a notice under DPT are close, in some circumstances HMRC are issuing notices where limited previous dialogue has taken place. In good news, the DPT contains some exemptions that may apply to many small and medium size U.S. groups.

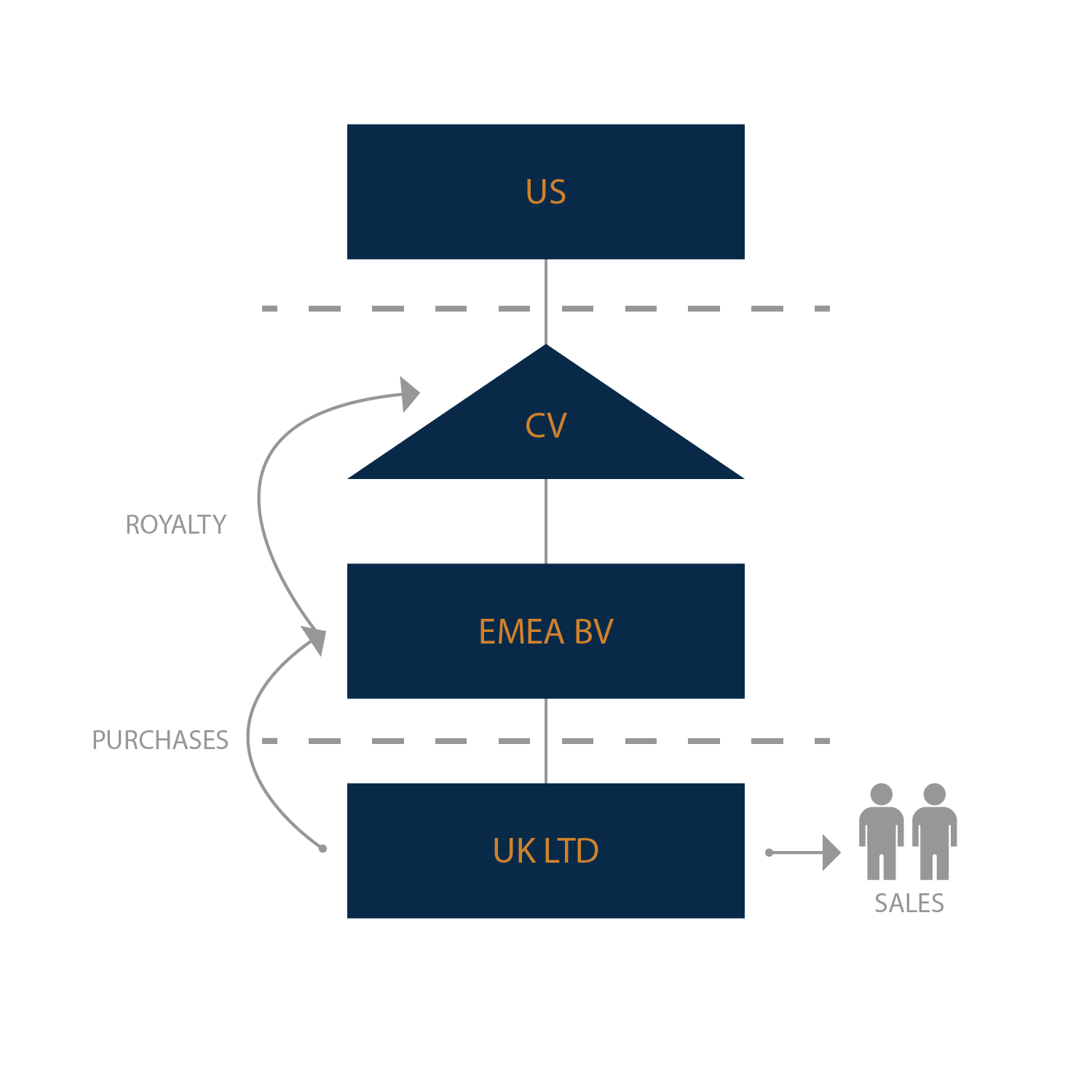

DPT addresses two common structures U.S. headquartered tech companies adopt for sales into the UK:

1. U.K. sales and marketing companies earning a low profit margin - but where there are significant sales of products or services into the U.K. by a low tax principal (e.g., Ireland or Luxembourg); and

-

U.K. distribution companies selling directly in the U.K. and earning a low profit margin - but buying in products or services from a principal, which may in turn be making large payments to a low tax company (as you might see in a Double Irish, CV/BV, or similar set-up).

In structure 1, DPT would be imposed on the low tax principal whose operations have been structured to achieve only a small U.K. taxable profit despite significant U.K. sales. In structure 2, DPT would be imposed on the U.K. resident distribution company whose transfer pricing arrangements with non-U.K. affiliates are not in line with HMRC’s view of the substance of the non-U.K. operations.

So which groups are at risk of falling within the DPT? Groups where the substance in the profitable company may be limited to servers and support functions (finance, legal, etc.) are particularly at risk, but the rules encompass a lot of other situations. In particular, the DPT can catch profit stripping where U.K. companies were previously more profitable and perhaps owned IP before being integrated into the current carefully planned supply chain. One of the key aims of DPT is behavior change, and companies at risk can often amend transfer pricing arrangements to ensure profits have not been diverted. In January 2016, for example, Google settled a long running transfer pricing enquiry with HMRC to the tune of £130m and stated that it would apply revised transfer pricing from 2015 onwards. And thus, ironically, Google itself has not been (and is unlikely to be) subjected to the Google Tax.

Authors: Richard Syratt and Claire Lambert

We’d love to get your thoughts: Has your company considered whether it may have any exposure under the DPT system? Have you set out an action plan to mitigate such exposures? Please call or email us and let us know!

To access all A&M Tax Minute issues, click here.