The Energy Transition in Australia: A Catalyst for Emerging Litigation Risks

Australia is in the midst of a monumental energy shift—one that’s reshaping industries, communities, and the very fabric of how we power our lives. This energy transition, driven by ambitious climate targets, technological advancements, and growing public demand for sustainability, is reshaping industries and creating new opportunities for growth. However, alongside these opportunities lies a complex web of legal and regulatory challenges that are giving rise to a burgeoning area of litigation.

As governments, corporations, and communities navigate the transition, disputes are emerging over issues such as land use, project approvals, environmental impacts, and the allocation of costs and benefits. The rapid expansion of renewable energy projects, including wind and solar farms, has sparked conflicts over land rights and community consent, while the decommissioning of fossil fuel infrastructure raises questions about liability and remediation. Additionally, the evolving regulatory framework and the integration of new technologies, such as battery storage and hydrogen, are creating uncertainties that could lead to contractual disputes and compliance challenges.

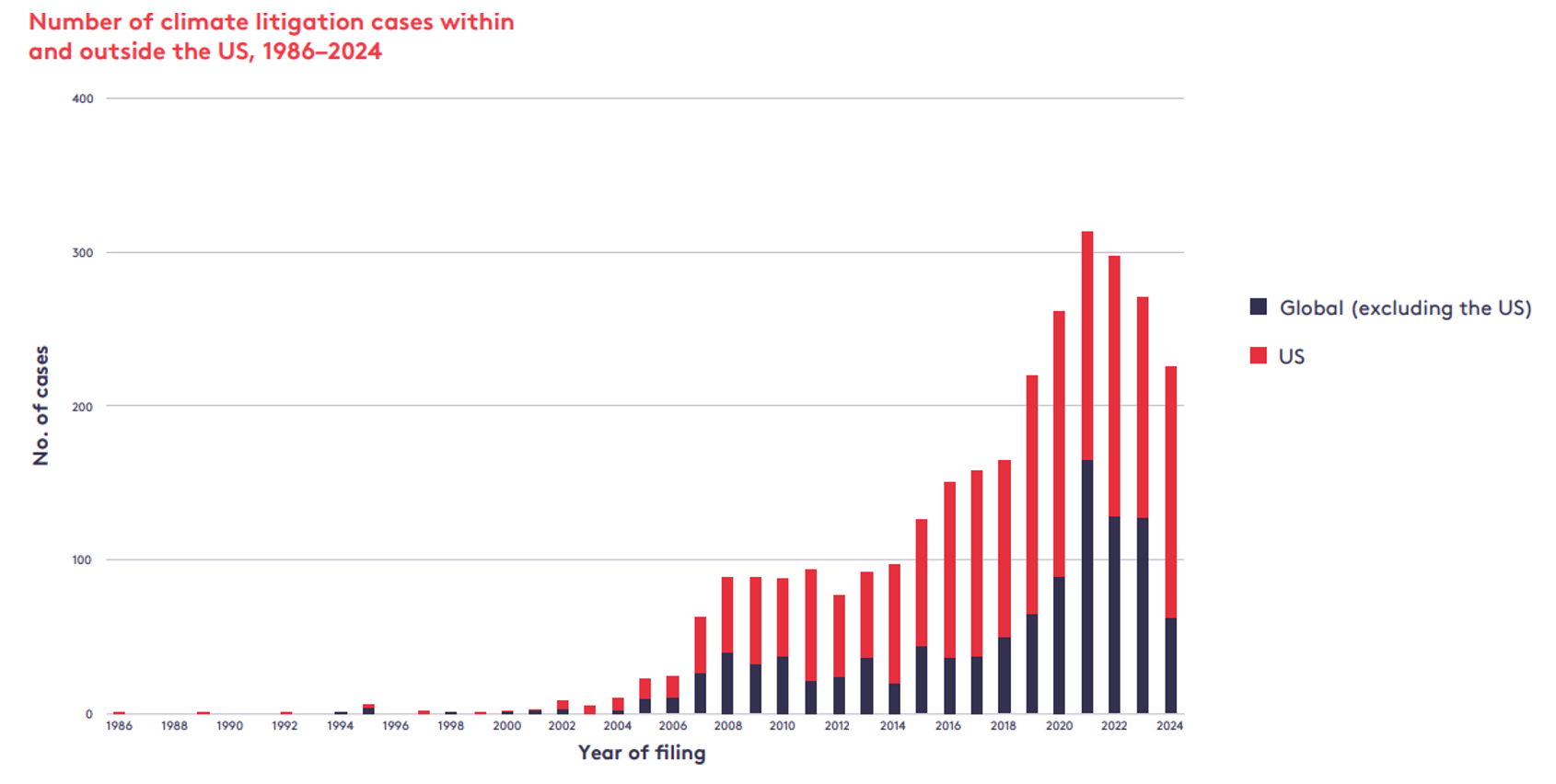

Let’s talk about the numbers. Australia is now the second most litigious country in the world for climate-related cases, with 164 lawsuits recorded as of late 2024.[1] These cases aren’t just statistics—they’re a reflection of a society demanding accountability, transparency, and action.

Figure 1: Number of climate litigation cases within and outside the US, 1986–2024 [2]

This article will delve into the key drivers of greenwashing and bluewashing within the context of Australia's energy transition, examining these issues through a forensic accounting lens. By uncovering the financial and operational practices that contribute to misleading claims of environmental and social responsibility, we aim to shed light on the risks these behaviors pose to stakeholders. Understanding these risks, from reputational damage to regulatory penalties and investor disputes, is essential for navigating the complexities of the energy transition and fostering accountability in this critical period of change.

Greenwashing and Bluewashing Definitions in Australia

Central to the emerging risks in Australia's energy transition are the practices of greenwashing and bluewashing, which have become focal points for regulatory scrutiny and stakeholder concern. According to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), greenwashing is defined as "the practice of misrepresenting the extent to which a financial product or investment strategy is environmentally friendly, sustainable, or ethical."[3] This deceptive practice undermines trust in sustainable finance and can mislead investors, consumers, and regulators about the true environmental impact of a product or strategy.

Similarly, bluewashing, as defined by the Australian Human Rights Institute, involves companies making exaggerated claims about their social and ethical commitments—such as promoting "slavery-free supply chains" or aligning with global initiatives like the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC)—without implementing meaningful reforms.[4] Bluewashing creates a false image of corporate social responsibility, often masking ongoing issues related to labor rights, human rights, and ethical governance.

Both greenwashing and bluewashing represent significant risks in the context of Australia's energy transition. They not only erode public and investor confidence but also expose companies to legal and reputational consequences. As the energy sector evolves, understanding these practices and their implications is critical for fostering transparency, accountability, and genuine progress toward sustainability and social responsibility.

The Fraud Triangle and Its Relevance to Greenwashing and Bluewashing Risks

The fraud triangle, a well-established framework in forensic accounting, identifies three key elements that contribute to fraudulent behavior: pressure, opportunity, and rationalization.[5] In the context of Australia's energy transition, these elements provide a lens through which the risks of greenwashing and bluewashing can be understood and analyzed.

Pressure arises from the growing demand for companies to demonstrate their commitment to sustainability and social responsibility. With investors, regulators, and consumers increasingly prioritizing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors, organizations may feel compelled to present themselves as leaders in these areas, even if their actual practices fall short. This pressure is particularly acute in the energy sector, where the transition to renewables is both a business imperative and a public expectation. Companies facing financial or competitive challenges may resort to misrepresenting their ESG credentials to attract investment or maintain market share.

Opportunity emerges from gaps in regulatory oversight and the complexity of verifying ESG claims. The evolving nature of sustainability metrics and the lack of standardized reporting frameworks create an environment where companies can exploit ambiguities to exaggerate their environmental or social impact. For instance, vague or unverifiable claims about carbon neutrality or ethical supply chains can go unchecked, providing fertile ground for greenwashing and bluewashing practices.

Rationalization completes the triangle, as individuals or organizations justify their deceptive actions. In the energy sector, this might involve rationalizing misleading claims as necessary to secure funding for renewable projects or to maintain public support during the transition. Companies may argue that their intentions are ultimately aligned with sustainability goals, even if their immediate actions involve misrepresentation.

Together, these elements of the fraud triangle highlight the systemic vulnerabilities that can lead to increased risks of greenwashing and bluewashing in the energy transition. Addressing these risks requires robust regulatory frameworks, enhanced transparency, and a commitment to ethical practices to ensure that the transition to a sustainable future is both credible and accountable.

Key Risks for Organizations in the Energy Transition

As organizations navigate the complexities of Australia's energy transition, they face a range of risks tied to greenwashing and bluewashing practices. These risks extend beyond reputational damage, encompassing regulatory penalties, legal disputes, and financial losses. Misrepresenting environmental or social credentials can lead to investigations by regulatory bodies, such as the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), and expose organizations to lawsuits from investors or stakeholders who feel misled. Additionally, the erosion of trust among consumers and business partners can have long-term consequences for market position and profitability.

To address these risks, organizations must critically evaluate their practices and ask themselves key questions, such as:

- Are our sustainability claims backed by verifiable data and evidence?

- Do we have robust internal controls and governance structures to ensure the accuracy of our ESG reporting?

- Have we conducted thorough due diligence on our supply chain to ensure compliance with ethical and environmental standards?

- Are we prepared to provide transparent documentation to regulators, investors, and other stakeholders if our claims are challenged?

Proactive Measures: Questions to Guide Risk Mitigation

To reduce the risks of greenwashing and bluewashing, organizations should adopt a proactive approach by asking themselves the following questions:

- Data Integrity and Verification

- Are we collecting and analyzing ESG data using rigorous and standardized methodologies?

- Do we conduct regular audits of our ESG data to identify discrepancies or inaccuracies?

- Transparency and Accountability

- Are we openly sharing our sustainability goals, methodologies, and progress with stakeholders?

- Do we have clear policies and procedures in place to guide ethical decision-making and compliance with regulatory standards?

- Employee Training and Awareness

- Are our employees adequately trained to understand the importance of accurate ESG reporting and the risks of misrepresentation?

- Do we have a culture that prioritizes accountability and ethical practices at all levels of the organization?

- Risk Assessment and Management

- Have we conducted a comprehensive risk assessment to identify vulnerabilities in our ESG practices?

- Are we actively monitoring changes in regulations and industry standards to ensure compliance?

- Stakeholder Engagement

- Are we engaging with investors, regulators, and communities to understand their expectations and address their concerns?

- Do we have mechanisms in place to respond to stakeholder feedback and adapt our practices accordingly?

By addressing these questions, organizations can identify potential weaknesses in their ESG strategies and take targeted actions to mitigate risks. This approach not only reduces the likelihood of greenwashing and bluewashing but also strengthens trust with stakeholders and ensures that sustainability efforts are both credible and defensible.

Read Past Raising the Bar Issues

[1] Joana Setzer and Catherine Higham, “Global trends in climate change litigation: 2025 snapshot,” Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2025, https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Global-Trends-in-Climate-Change-Litigation-2025-Snapshot.pdf.

[2] Ibid., p. 11.

[3] Joe Longo, “Greenwashing: A view from the regulator,” ASIC, Keynote speech, RIAA Conference Australia, May 2, 2024, https://www.asic.gov.au/about-asic/news-centre/speeches/greenwashing-a-view-from-the-regulator/#_ftn4

[4] Samuel Pryde and Justine Nolan, “Explainer: What is greenwashing and bluewashing, and why should we care about it?” Australian Human Rights Institute, n.d., accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.humanrights.unsw.edu.au/research/commentary/explainer-what-is-greenwashing-bluewashing

[5] “Fraud Triangle,” Corporate Finance Institute, n.d., accessed July 21, 2025, https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/accounting/fraud-triangle/